A Beginner's Guide to Measures in Music Theory

June 19, 2024 - Music theory mystery solved! This guide breaks down measures for beginners, making rhythm a breeze. Master counting & understand song structure.

Are you looking to dive into music theory, but don’t quite know where to start?

Familiarizing yourself with the basic symbols and elements of sheet music is a great jumping-off point. And while it may seem daunting at first, it doesn’t have to be.

In this guide, we’ll talk about measures and how they relate to rhythm and time signatures. We’ll also look into the idea of basic song form, and discuss how you can use measures to make musical phrases, which will help you write songs more quickly and easily.

Once you know the basics, it’s simple to see how to lay out a new song in notation.

Let’s get started!

What is a Measure in Music?

In music, a measure (also known as a bar) is a small segment of musical content that is separated by the next with a vertical line. This vertical line is called a barline.

It’s believed that the first measures were placed in music around the 15th century in Europe (Britannica).

Barlines

There are several types of barlines: single (regular), double barlines, ending barlines, repeat signs, and dashed barlines.

Standard bar lines have a single line, whereas double (fittingly) have two.

This barline marks a pause in musical thought.

Double bar lines tend to denote the end of a section or significant phrase, but not the end of the song.

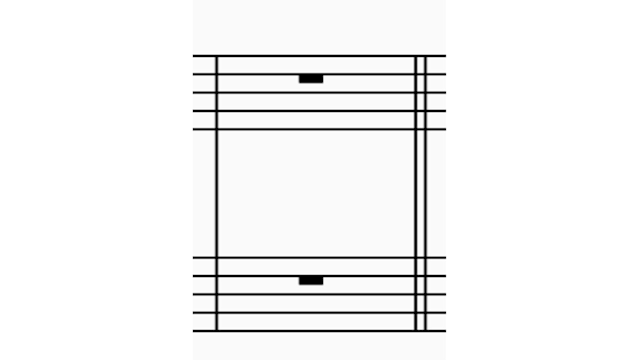

End barline

If you see two lines in bold like the picture above, that means it’s the end of the song.

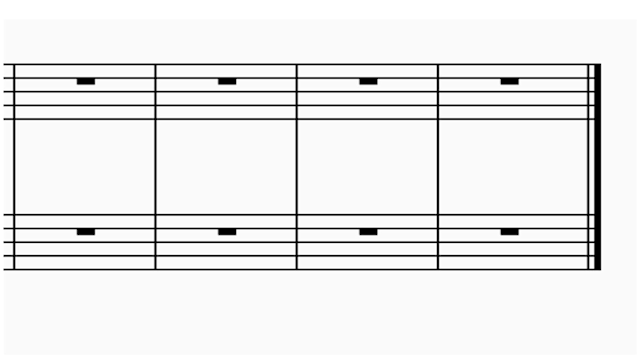

These barlines are repeat signs. See how they act as end-caps.

Repeat signs are also technically a type of barline. These measures look like double bar lines with two dots and are typically bolded. Repeat signs come in a set, the first one shows you where the repeat begins, and the other shows where it ends.

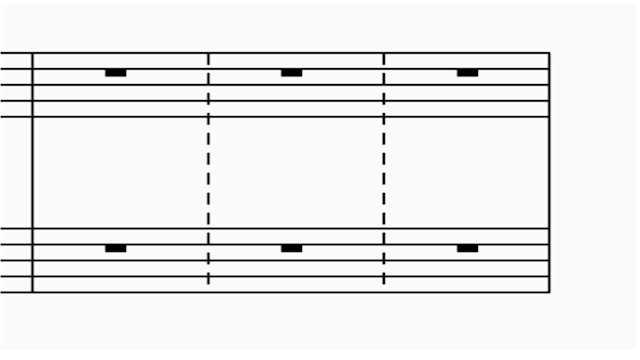

These dashed lines help composers organize complicated rhythmic ideas.

There are also dashed and dotted barlines. They are the least common type of barline. These help divide measures to make rhythms in complex time signatures easier to read.

Why Do We Use Measures?

Measures help us to stay organized in music. Since many pieces are so long (think: Beethoven’s Symphonies) bars are a necessity for musical collaboration.

Without measures, we wouldn’t be able to record organized music with large groups of musicians. This is because measures provide a reference point in a sea of notes allowing composers to add in rehearsal markings as larger landing points. You can also think of measures as a picture frame that captures a small chunk of rhythms in a piece, or even as a unit of time.

Measures can also give allotted space for improvisation- or as jazz cats say, “comping .The number of measures people originally traded in improv. started out with groups of 4 bars at a time. (For those music-history buffs out there, it began in New Orleans with ‘trading 4s’ in a call-and-response style).

The more you listen, the more you’ll notice how Western music shows up in sets of 4 measures at a time. It is a theme that reoccurs in many genres.

Determining Measure Length: Time Signatures

The number of beats and the time signature will determine how long each measure is.

There are two main types of meters: simple and compound. In simple meters, beats can be divided evenly.

A 4/4 measure can fit 4 quarters. The quarter notes are the main beat so time signature is simple.

There are a plethora of simple meter songs out there. From “Stronger” by Kanye West, to Sabrina Carpenter’s “Espresso” and even Beethovens’ “Ode to Joy”.

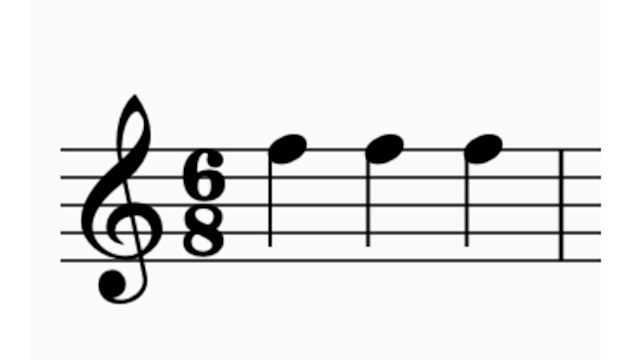

A 6/8 measure can fit 3 quarter notes or 6 eighth notes. The main beat is the eighth note.

In compound meters, beats can be divided into 3. One common example of a compound meter is 6/8. Queens' “We Are the Champions”, Taylor Swift’s “Dear John” and even Mayday Parade’s ‘Terrible Things” are in this compound meter (6/8) which can be divided into either two or three.

Dividing the Fraction & Where to Find Meters in Music

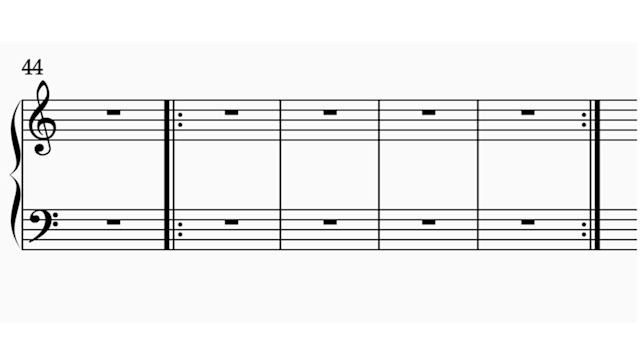

The numbers/fraction on the left is a time signature.

Time signatures are also sometimes called meters, and can be found on the left side of the music after the clef symbol.

The bottom number in a time signature denotes the main note value that is being counted. In 4/4 that means we are counting quarter notes. 1 divided by 4 equals 1/4, giving us a quarter of a beat.

The bottom number in the time signature is always going to be a multiple of 2. If we were to look at a piece in 4/2, a half note would be the main beat.

The top number will tell you how many beats are inside the bar.

Common time

The most common time sign signature in the West is 4/4: hence the name common time. 4/4 may appear as a big C on the left side of the music. Other popular time signatures include 2/4, cut time. 3/4 and 6/8.

Measures and Counting

Counting and subdividing written out in 4/4 (aka common time) in an American counting style

If you’ve ever crocheted, you know that the most important part of making a hat is counting. Whenever my cousins or parents grew frustrated with the project my grandmother was trying to teach them, she simply would say ‘You’ve got to count, honey!’.

The same goes for music. Nobody makes it into the LA Philharmonic without counting, let alone the community band.

So here’s some tips on how to do it.

Start counting the smallest realistic beat

Practice and count until you get comfortable

Then, start counting the bigger (macro) beat

As we discussed earlier if we are in a typical 4/4 time signature, there are 4 beats per measure. Everything is quarter notes. In this case, the biggest beat you’d want to count is 1,2,3,4. The smaller beat you might start with is the eight note (as long as the tempo is a walking pace) you can count a measure as 1+2+3+4+.

There are loads of different rhythm counting systems: Eastman, Traditional American, Dalcroze… Choose one you like and stick with it as you learn. As you get more comfortable with the song or piece, if it’s fast enough you can start feeling the song in whole measures rather than counting each individual eighth note or quarter note.

Feeling into the rhythmic structure of a song will eventually give rise to more emotive phrasing and playing, so keep counting and pushing yourself.

The Power of Intentional Listening

Sometimes playing a new instrument and counting measures at the same time can be overwhelming. That’s why intentional listening is so important. Even if you haven’t read notes yet, you can still pull up some scores of your favorite tunes on YouTube and follow along with the measures and broad strokes of the piece.

Listening to just one song a day while following along to a score will make a difference.

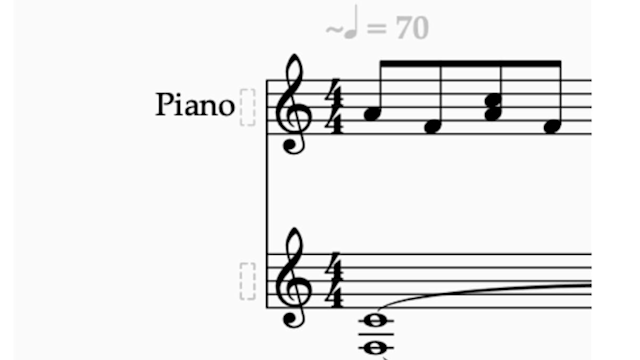

The Kid Laroi & Justin Bieber — Stay (Piano Sheet Music)

Measures and Song Structure

Now that you know all about the measures/barlines, let’s apply them to the concept of song structure.

Have you ever noticed how top-40 pop songs tend to be 3 ½ minutes in length and around 120-bmp? Popular tunes tend to follow a similar song structure: intro/verse, pre-chorus, chorus, (sometimes) bridge, chorus (sometimes double chorus), outro. This can all be related back to the little measure because each section tends to be in a grouping of 4.

Measures help us set up everything- From classical music’s sonata form to a pop songs’ AABA setup, and everything else in-between.

Setting Up a (Song-Form) Song

To make songwriting less daunting, I like to look at it as a blank score in groups of measures. In your favorite notation program or DAW lay out a song-form structure. Here’s an example:

Intro- 4 bars

Verse-16 bars

Pre-Chorus-8 bars

Chorus-8 bars

Bridge-8 bars

Double chorus- 16 bars (two 8-bar patterns repeated)

Sectioning out content into measures like this can help you to see how long your musical content needs to be, and where you need transitions in your music.

Whenever I go to write a new original (or even a coversong) I lay it out in sections to make it easier to see.

What Are Phrases?

I’ve mentioned musical phrases several times in the article- but what are they?

Phrases are ‘sonic sentences; that typically span several measures in length. In language, sentences take a pause or come to a stop before introducing another idea. The same goes for music.

In the children’s song “Mary Had a Little Lamb” the first phrase would be “Mary had a little lamb, little lamb, little lamb” and the second phrase would be “Mary had a little lamb, her fleece was white as snow”.

The above song-form setup lends well to 4-bar phrases.

Phrases and measures go hand-in-hand. The next time you start a piece, try beginning it with an 8-measure phrase or thought. You’ll likely soon find that one musical sentence can become an entire tune if you let it branch out into different variations and motifs.

Incomplete Measures/Pickups: How They Work

When you’re reading music, you might notice that there are times when a piece/song starts with one note in the first measure. This is called a pickup note. The ‘Hey’ in “Hey Jude” by the Beatles is a good song to listen to in order to get a feel for what a pickup note is.

Pickup notes are just one example of incomplete measures: Incomplete measures happen when the bar does not have as many beats as the time signature denotes.

Breaking the Norm: Pieces Without Measures

Measures give us a strong sense of phrasing- but sometimes, musicians don’t want that effect. In avante-garde music or older baroque pieces that are intended to be flowing, with no implied downbeat, measures can be our enemies. That’s why flutists sometimes re-write the famous piece “Syrinx” to have no barlines at all.

The following composers, eras, and pieces tend to have a lack of strictness in their composition:

“Unmeasured Prelude for Harpsichord” - Couperin

”Parallaxis Forma” Catherine Lamb

“Three Voices”- Kris Mariasy (recorded by Aleah Fitzwater)

Select works by Onute Narbutate

“Fontana Mix” -John Cage

1960’s and 1970’s free rhythm pieces

Use Your Newfound Knowledge to Make Something New!

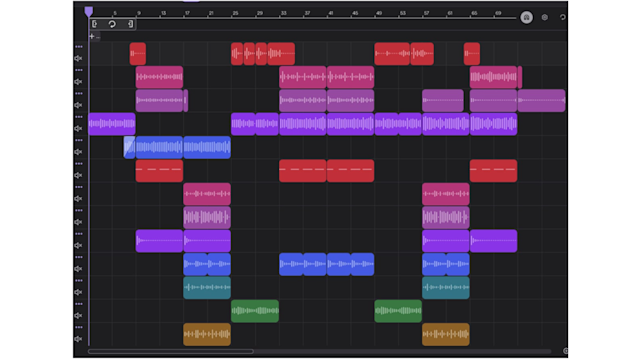

Even if you don’t read music, you can take this concept of measures and run with it by setting up a visual score in our DAW, Soundtrap.

If you open up any of our sample tracks (like Kontrol above) you can visually see how the measures and phrases are in groups of 4. Take inspiration, and create a new track of your own today with Soundtrap! We also have pre-made templates that already have the measures and song form laid out here.

You can also take digital music XML files (from Sibelius, Flat, etc) and export them directly into our cloud-based platform.

You now know and understand a crucial element of musical/rhythmic structure- so get grooving and make something today!

About the author

Aleah Fitzwater is a multi-instrumentalist, songwriter, music journalist, and blogger from Temperance, United States. Aleah holds a Pk-12 instrumental music education degree. Her main instruments are flute, piano, drums, bass, and guitar.

Get started with Soundtrap today!